|

| Evanston Art Center. Photo Credit: Polly Solomon |

Gabriel FLASH Carrasquillo, who is an engineer, artist, photographer, and educator, shared some of his vast archives of Chicago-based graffiti and street art that go back to the 1970s. He is in the process of collaborating on a book that chronicles the history of Chicago graffiti from the 1970s to 2003 (when the first Chicago Meeting of Styles) took place. It was a treat to see early throw ups on the Red Line Chicago stop; Logan Square and Wicker Park before gentrification; and the evolution of Chicago style. Flash noted that "sprinkles of color and fades..dustings of pinks and blues" versus the screaming reds and oranges of early New York subway pieces distinguished Chicago early on. Flash started writing in 1983, after the moving "Style Wars" came out, and was influenced by Chicago youth who had returned from New York after picking up graffiti styles. He received the name "Flash," because he was known for carrying around a 35 millimeter camera. He was part of ABC (Artistic Bombing Crew), who were among the first Chicago-based crews, and painted all over the city. After retiring in 1987 he returned to the scene in 2003. Flash's retirement coincided with the disappearance of a "whole generation of writers." Although when graffiti started in Chicago it was met with confusion or indifference, "CTA workers would say 'Good night writers,'" Flash had joked, by the 1990s it was an all out graffiti war.

|

| Flash autographing our poster. Evanston, IL. Photo Credit: Caitlin Bruce |

This is Flash's mission, creating space for the old school and the new school, which will also educate a broader public about graffiti's artistic potential. Flash curates a set of walls in Logan Square, the neighborhood where he "did his damage" in the 1980s as a way to give back.

"Project Logan," includes a large wall with 174 sections, a slightly smaller crew wall, and a yet slightly smaller dedication wall, on which works stay up for a long period of time. Finally, there is a little "two spot" section which is exactly that: two spots, for two people, which stays up for two weeks at a time. Yet, even during the seemingly short period of two weeks the wall, which is viewable from the blue line, will be seen by over two million people. Project Logan is a visual extension to Flash's book project, where he displays work from artists who were pioneers but part of that "lost generation."KLTA was one of the first artists who were displayed on the wall, a street artist who, between 1983 and 1987 had works on over seventy rooftops throughout Chicago.

Creating legal venues like that of Project Logan is crucial to giving youth an outlet. Flash explained: "They will always have the paint, and if they don't have a legal spot...they will paint somewhere else." Flash's work at Project Logan exhibits a relationship of stewardship between the old school and the new school: older generations of graffiti artists, and younger. Such a relationship involves imparting "a culture and a code." In cities like Chicago, Flash argued, many non initiates are blinded by a culture that is imparted by strict anti graffiti laws, preventing artists (and art lovers) from benefiting from a market that is vibrant across many cities outside Chicago. The past mayoral administration(s) continued this culture of demonization, even buffing permission walls, or "blowing up paint cans," a "no write" policy that fomented an antagonistic relationship between city officials and writers that is captured in the film "I Write on Stuff." Flash contrasted Chicago's anti graffiti culture with that of Paris, where, he suggested "permission pieces stay up for a hundred years."Such a climate is changing, Flash added, hopefully, with the new mayoral administration.

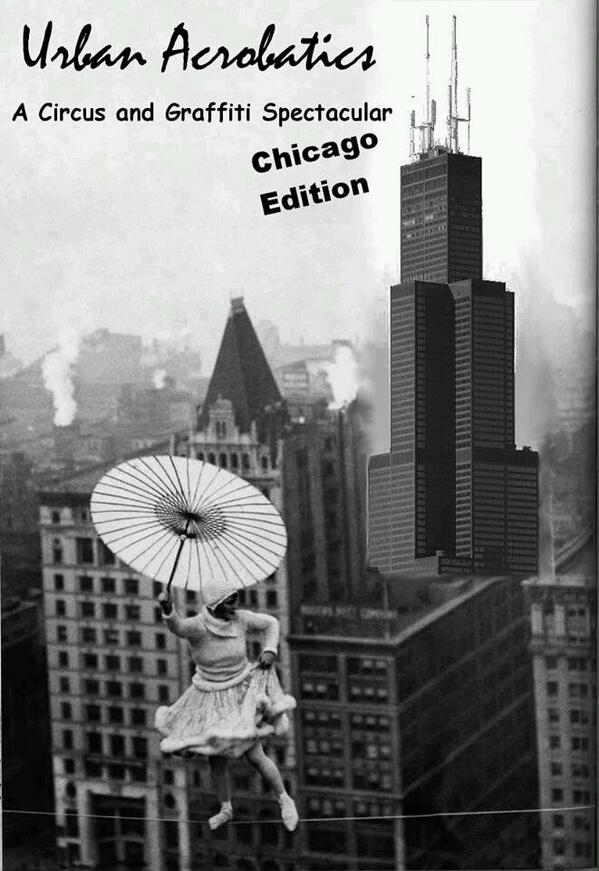

Roy Gomez-Cruz artfully discussed some of the spatial and social dynamics of learning about circus art in Chicago, performance scenes that are inflected by changing industrial landscapes, and bodies that engage, resist, and transform prevailing gender binaries. However, learning how to do circus acts involves putting the body on display in ways that are uncomfortable, involve judgment, and "risk and failure." The idea of learning a public art genre that requires the practitioner to confront ongoing possibilities of failure and risk resonates with Flash's formulation of the risks of writing, in terms of the ephemerality of the work, social judgement (and misjudgement), and the risk of it being denigrated. "Circus training lets the body become spectacular," Roy opened, "through body to body encounters...[that] puts bodies at risk" in ways that are physical and also social. Focussing on Aloft Loft, Roy analyzed his experience as a newcomer and a male in a largely female aerial acrobatics community as an encounter with discomfort, uncertainty, and feeling not at home. However, such feelings of being out of place are not necessarily bad, they provided, in his account "opportunities to exercise self reflexivity." The circus world(s) Roy engages largely engage in an avant-garde form of circus, and he has been attending shows regularly since 2011. In one such show, Roy observed Aloft Loft founder Shayna Swanson manipulating a German wheel in a masterful performance of strength, endurance, and industrial materials, "dominating gracefully the circus apparatus [in] a performance [that] is an extension of the landscape outside." As a new practitioner, Roy notes that the "body is mute as a new practitioner." This idea of being ineloquent in a new aesthetic form carries across genres-- in graffiti new writers must practice the tag over and over to get it down to a deft art. Although circus training involves risk and vulnerability, Roy concluded, perhaps such training may "allow us to meet others."

|

| Image compilation by Polly Solomon |

In both genres practitioners use movement in the creation of their art (swinging from trapeze, dance, acrobatics for circus, bent knees whole arm movements and sometimes climbing out of the way places for graffiti) but also in the circulation of their own bodies. Referencing our conversation with Melon the other day, Polly remarked that in doing graffiti some writers are so close to the micro details of their work that when they step back they are amazed about what has been created. In a similar sense for circus performers it is difficult to see the visual picture one is painting while doing an act. Notably, the train figures as an important trope in graffiti and circus lore. Additionally, Polly noted that in both graffiti and circus culture there is an intense reliance on one's crew or troupe or team. Such reliance comes out of necessity, one needs a spotter, or a lookout, or a partner for a complex pose or act, but also for a sense of community and identity. In many communities of practice the practitioners have a sort of volitional family.

Polly defined circus as: "a release from everyday mundane into extraordinary for audience for feats not achievable for everyday person such that it takes audience out of their world, [feeling] different than [just] walking down the street." She concluded by emphasizing that creativity is about inspiration, which is quite literally taking breath. "One of the ways that we can inspire [lies] in how we treat the next generation coming up, and teach them and let them teach us." This generational obligation, or ethic of care, resonated with Flash's "Project Logan" walls, as well as the potential Roy sees in circus enabling practitioners to teach and learn body-to-body encounters that may be generous and transformative. In Chicago, a city of industrial blocks, sharp class and racial division and inequalities, and sprawling neighborhoods, both circus and graffiti practice offers ways of being in common that rest on respect, risk, vulnerability, and inspiration that may shape more equitable, and more oxygenated urban spaces.

No comments:

Post a Comment